With latex gloves on and syringes at the ready, Bryant’s Health Services staff spent last Thursday administering flu shots in the Unistructure’s Mezzanine. Rolling up one sleeve and experiencing a quick pinch, students, faculty, and staff walked away with more than just a Band-Aid — they now had a strategy to fight the flu.

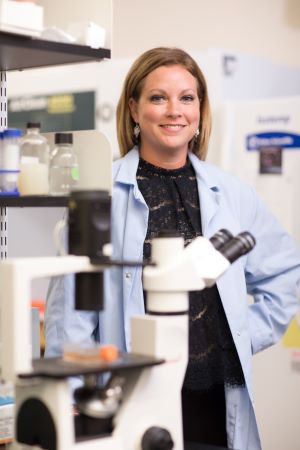

“The virus loves communities where people are close together because it's easier to jump from one person to the next. Think classrooms, sports teams, locker rooms, concerts, or living spaces,” says Biological and Biomedical Sciences Lecturer Stephanie Mott, M.S.

Flu season, which begins in early fall, can leave people sick for 10 to 14 days. With peak infection rates occurring between late-November and March, health officials recommend individuals receive an annual flu shot in September or October; those who receive a shot any earlier could experience waning antibodies during the virus’ active periods.

“You really don't want to get sick,” Mott says. “If you have the flu, you're more susceptible to other infections. A lot of people who have the flu will then get an ear infection, eye infection, or pneumonia, so if you can eliminate the first infection, then you won't get the second.”

to prevent full-scale versions of the infection

and reduce hospitalizations and deaths.

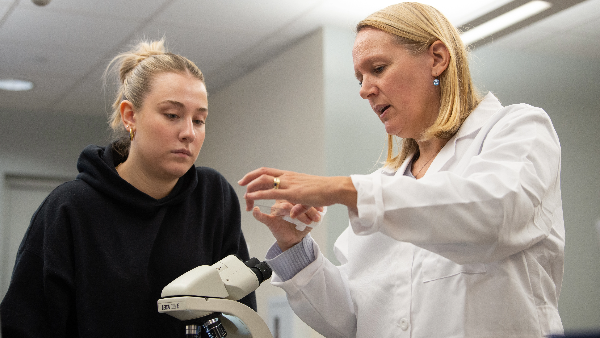

School of Health and Behavioral Sciences Director Kirsten Hokeness, Ph.D., notes that the flu vaccine seeks to prevent full-scale versions of the infection and reduce hospitalizations and deaths. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, vaccinations during the 2019-2020 flu season prevented approximately 7.5 million influenza illnesses, 3.7 million influenza-associated medical visits, 105,000 influenza-associated hospitalizations, and 6,300 influenza-associated deaths.

While the vaccine’s core stays the same each year, there are aspects that change depending on the seasonal variant.

“You have to predict in advance what virus strains are going to be heavily dominant in that seasonal flu wave, so you're constantly using analytics to look at across the globe of what's happening,” says Hokeness, adding that scientists use dominant strains to make the vaccine.

Variant predictions occur a year in advance; it takes that much time to grow the virus, produce the vaccine, and distribute it to the public. Hokeness says the vaccine manufacturing process begins with growing the flu virus in eggs and incubating the eggs before extracting the virus; this method has been used for more than 70 years. The vaccine can also be created through recombinant technology and a cell culture-based production process.

If the strain circulating the population and the vaccine are a match, the vaccine should prove effective. Hokeness notes that problems occur when there's a diversion during the seasonal flu cycle and newer or different variants arise — these are the years where the vaccine's not as effective.

Flu symptoms often include respiratory congestion, coughing, and fevers, and those who are most impacted are young children, those over 65, and the immunocompromised. Mott explains that as the virus circulates the population, humans develop immunity against the infective process, which stops the virus in its tracks and forces it to change itself to sneak around the immunity. Vaccine side effects should be minimal and may include soreness from the needle prick and tiredness the following day.

“The vaccine exposes a person to a small part of the virus that cannot make you sick. By giving the body a portion of the virus, you’re telling it, ‘Okay, this is coming your way,’” Mott says.

Vaccine protection kicks in two weeks after the injection since the body needs time to build antibodies. Hokeness adds that as infections are encountered, the immune system mounts a fighting response; the body will remember this virus exposure — causing it to have a quicker and more vigorous response the next time.

Bryant’s Health Services will hold a flu clinic on Nov. 8 from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. in MRC 3.