It’s a Thursday morning in an Academic Innovation Center classroom and Associate Professor of Economics Aziz Berdiev, Ph.D., can barely catch his breath between answering the multitude of questions high schoolers have about macroeconomics. With every answer he gives, two more arms shoot up across the tiered room. It’s Day 4 of Bryant’s Precollege Summer Economics Program and the group is learning about gross domestic product (GDP). As Berdiev explains how GDP measures the market value of all final goods and services produced in a country for one year, he calls on one of the raised hands in the back of the room.

“Say a car is made in 2020 but doesn’t sell until 2021. Would you measure the GDP in 2020 or the following year?” the high schooler asks.

Berdiev says the vehicle would be counted in GDP for 2020 and launches into a longer explanation on inventory investment.

“When the clock hits midnight and it becomes a new year, the car company has to buy the cars they produced but didn’t sell,” says Berdiev, noting that — in macroeconomics — there must be equality between what is produced and spent.

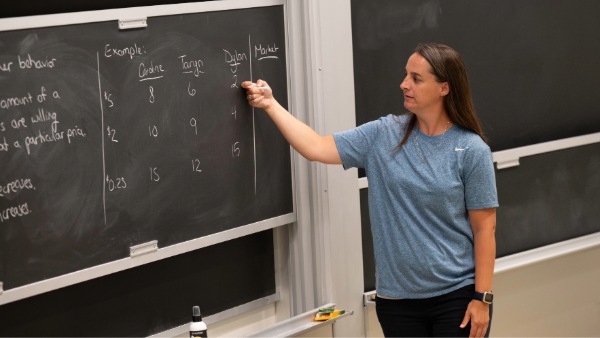

Twenty-eight pairs of eyes eagerly take in what he’s saying. When something stands out to them, they immediately grab their pencils, hunch over their desks, and scribble into their notebooks. Berdiev moves over to the white board, picks a marker, and starts teaching the group how to calculate nominal GDP and real GDP.

Introduction to college life

Celebrating its fifth year, Bryant’s Precollege Summer Economics Program welcomes high schoolers to campus for a five-day intensive camp where the teens learn basic and advanced economics, develop data analysis skills, analyze current policy issues, and engage with Bryant faculty for six hours each day. Students accepted into the program are eligible for full and partial scholarships and earn a certificate of completion at the program’s conclusion. This year — under the direction of Berdiev, Associate Professor of Economics Laura Beaudin, Ph.D., and Economics Lecturer Allison Kaminaga, Ph.D., — teens study opportunity cost, supply and demand, data analysis, macroeconomics, and regression analysis.

“Precollege programs allow high school students to get a sense for college life. They meet professors and engage with challenging college-level academic material, which enhances their knowledge in a field of interest,” says Beaudin. “They also have the opportunity to enjoy campus facilities — including the library, study lounges, the gym, and the dining hall. These experiences can help students feel more comfortable when transitioning from high school to college.”

In addition to learning basic economics principles, high schoolers tour campus and hear from various guest speakers. This year, the group heard from Bryant University President Ross Gittell, Ph.D., Assistant Vice President of Student Life Jana Valentine, Director of Career Services Veronica Stewart, College of Arts and Sciences Associate Dean Denise Horn, Ph.D., College of Business Dean Todd Alessandri, Ph.D., and Vice President for Strategy and Institutional Effectiveness Edinaldo Tebaldi, Ph.D.

Crunching numbers, analyzing data

After their group discussion on GDP, Berdiev moves on to inflation and the labor market. Setting students up for their next project, Berdiev pulls up the World Bank Database on the room’s projector and tells them that — within groups — they will pick two countries and calculate eight variables, which could be anything from the country’s unemployment rate to labor force participation. Sending them off into breakout rooms, they have half an hour to work on their calculations and create a PowerPoint presentation of their data that they will showcase to their peers.

“Group projects give students the opportunity to develop social skills necessary for college and the workplace while also allowing students to meet new people and develop friendships,” Beaudin says. “By the end of the week, students will have learned how to use both theory and data analysis to suggest solutions to issues of economic inequality while building important quantitative, qualitative, collaborative, and communication skills.”

The timeframe may be short, but the teens are up for the challenge. All week, they’ve gone back and forth from learning in the classroom to applying what they’ve discussed. Just that morning, they presented their work on data analysis related to housing, health, and gender inequality in sports. Throughout the next 30 minutes, faculty members pop into the breakout rooms to answer questions as students huddle together to calculate and compare data between countries. Eventually filtering back into the classroom, the high schoolers exude a level of confidence that wasn’t present earlier in the week. Their self-assurance is due, in part, to accurately finding variables like nominal GDP and real GDP but, mostly, it’s the result of discovering their budding passion for economics.