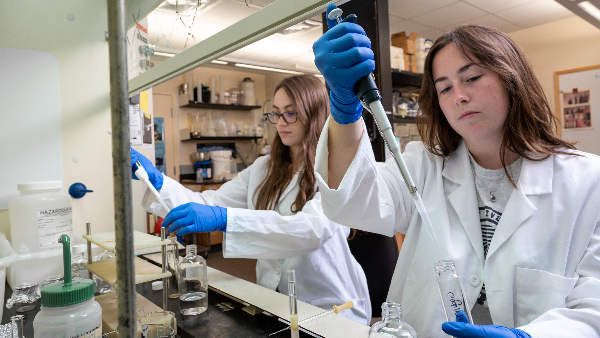

If you need to find Jillian Sylvia ’24 or Jenavieve Lyon ’26 this summer, look no further than Bryant’s research labs. The two School of Health and Behavioral Sciences students received $7,300 each from the NASA Rhode Island Space Grant Consortium for two projects and are working to develop technologies and lab protocols meant to help up-and-coming space programs.

Sylvia, a Biology major and seasoned summer research fellow, is creating new techniques to characterize climate on Earth’s past and present landscapes. The methods she develops could eventually be applied to Mars rock samples to look at the planet’s preservation.

Meanwhile, Lyon — an Environmental Science major engaging in her first summer research experience — is using rock and sedimentary samples to study past climate changes and apply this information to the climate changes humans are experiencing today.

“I’m really focused on different sustainability practices and how what we’re doing in the lab can affect what goes on in the real world,” says Lyon.

Since 1991, the Rhode Island Space Grant Consortium has provided undergraduate and graduate students with funding to encourage space-related science as a vehicle for enhancing scientific literacy among educators and their students. Grant recipients from Rhode Island’s colleges and universities complete research over summer break and present findings at a symposium the following spring. Through this opportunity, students network with the science community, learn from peers, and hear about graduate school programs and professional opportunities.

“Everyone knows NASA; their programs are fascinating, and everyone’s interested in space and life beyond Earth,” says Biological and Biomedical Sciences lecturer Robert Patalano, who is mentoring Sylvia and Lyon. “The fact that Bryant can play a small part in that is really exciting.”

Since NASA’s rover is currently collecting rock samples from Mars to eventually return to Earth, the two women are using rock and sedimentary samples from Clarkia, Idaho, a Miocene-era lakebed and field site that is a potential correlate for past environmental conditions on Mars. After isolating lipids and plant waxes from the sedimentary samples, Sylvia and Lyon will look at individual organic compounds and infer what they say about the past — such as what plants lived in the area, relative temperature and rainfall, or which microbial communities were present.

“It’s important to share this information about past or present environments to help predict where we are going in the future,” says Sylvia.

The emphasis on climate change is particularly important for this research. Patalano says 15 million years ago, Clarkia’s carbon dioxide (CO2) levels were 500 parts per million (ppm), and, at that time, the Arctic was covered in forest and woodlands. Today, because of human activity, CO2 levels have hit 424 ppm and driven global temperatures higher. He adds that humans have not seen an ice-free Arctic in their 2.5-million-year evolution.

“We’re going to need to learn from the past and know how different ecosystems responded to changing temperatures because there are going to be large parts of the world that we’re not going to be able to live in or grow food,” Patalano says.

Working in Bryant’s research labs Monday through Friday, Sylvia and Lyon will venture to Idaho in late July for field site research in Clarkia. Patalano says the grant allows for collaboration with other labs and travel opportunities, exposes students to the lab setting, and helps them develop skills and gain confidence in the lab.

“I’d encourage other students to seek these opportunities,” Sylvia says. “I think people are afraid that they don't have experience and won’t do well, but this is a safe space to get that experience.”